Technology To The Rescue

People are bad at random – we even have a tendency to find patterns where no intentional pattern exists (seeing a face in the stones on a wall is a common example). So, when forest managers are working to recreate the complex, seemingly random patterns found in nature, how do they do it?

They start with science and statistics. Yes – statistics can help you get surprisingly close to the complexity of nature (see my recent blog for background). Even so, after you determine what a more natural forest would look like in your area, there’s the challenge of implementing that on the ground.

I’m joining the Tapash Forest Collaborative for a workshop organized by the Nature Conservancy’s Ryan Haugo and led by the University of Washington’s Derek Churchill to see first-hand how a new app allows them to recreate spatially diverse, resilient forests on the ground.

" We realized we need to do something with these stands, or we’ll lose them all to insects, disease, and wildfire. "

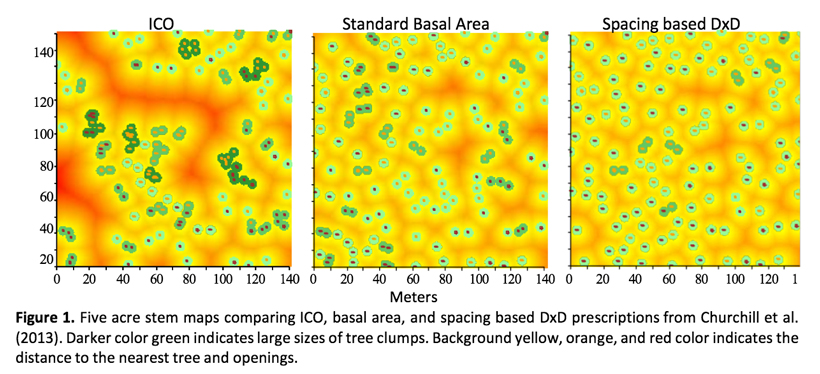

Rod PfeifleWe gather in Cle Elum, Washington to learn about the science behind restoring a forest to a more natural pattern of individual trees, tree clumps and forest openings (ICO). During the workshop local foresters have an opportunity to practice using QuickMap, a forestry app created by Churchill’s team to implement the ICO approach to ecological restoration thinning in dry western forests.

In the conference room, we look at aerial images and stem maps of old-growth forests in similar climates – these will provide the reference conditions for the healthy mosaic we hope to restore. Looking at the aerial images of forests and stem maps of the individual trees, clumps and openings, I can easily see the difference between a homogenous patch and one that’s spatially diverse.

In the Thick of It

However, once we arrive in a large clearing among Douglas firs and Ponderosa pines, the old saw about not seeing the forest for the trees becomes all too real. How will we decide which trees need to be thinned without the benefit of a birds-eye view? Undaunted, the forestry professionals around me gather for a briefing on the plans for this forest.

Rod Pfeifle of the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife leads with background on the forest and management goals for the future.

“The last harvest in this stand was 35 to 40 years ago. We realized we need to do something with these stands, or we’ll lose them all to insects, disease, and wildfire,” Pfeifle said.

This forest is being managed for conservation and wildlife habitat. The planned management will be mechanical thinning hopefully followed by burning, so we’ll need to mark which trees will not be cut in order to recreate a resilient spatial patchwork – yes, under some circumstances, thinning forests can be better for conservation in the long term.

We are instructed to keep any very old or very large trees. Another important goal is to keep and create wildlife trees, dead or unusually shaped trees that birds and other wildlife rely on for nesting and foraging opportunities. If there aren’t any around, we can mark trees that have a “catface” or scar to let tree removal crews know they should remove the top of the tree, but leave a “snag” behind, which will become a new wildlife tree.

Some threatened spotted owls still live not far from this area, so we’re keeping an eye out for and preserving any areas that could be good habitat for them to expand to in the future.

Keeping all of this in mind, we’ll use QuickMap to decide how many trees we need to remove and which trees we should keep in order to recreate a resilient spatial mosaic in this forest.

QuickMap to the Rescue

Each team gets a tablet with the QuickMap app and a few cans of neon orange paint. Measuring tape is also a must, but these foresters come prepared, the typical “uniform” includes a utility belt complete with tape measurer and a spot to hang a paint sprayer, a hard hat, and a safety vest with built in pockets all around the bottom.

We huddle around to look at the app and discuss the layout and goals for our five-acre practice plot (pine forest surrounding a rocky clearing on a slope).

The app has already been updated with information about how many individual trees and clumps a naturally diverse five-acre plot in this area would be statistically likely to contain.

As we ascend, the group discusses which trees to mark as “leave trees” (those that will not be removed). Leave trees are marked with paint, measured, and the data is entered in the app as individuals or clumps – the number of trees in a clump and the average diameter is also recorded. QuickMap uses a color coded system to let crews on the ground know in real time as they approach an appropriate number of individual trees and clumps for the reference areas.

It’s not important that each team have exactly the number of recommended individuals and clumps for their region. Depending on factors like soil conditions and wildlife goals, some groups end up preserving more clumps, while others preserve more individual trees – the more acres that are covered, the more the final result averages out to create a diverse spatial mosaic that will keep the forest resilient to fires, pests, and a changing climate.

Even though it’s our first time using the app, our five-acres are mapped in just a couple of hours. An experienced two-person team can mark 10-20 acres in just one day. The app is still being improved, but once it is complete Churchill will make it freely available so that people in different places can adapt it to their needs and make it their own. Speed is of the essence since millions of acres of America’s forests are too dense compared to reference conditions, making them prone to uncharacteristically severe fire and disease.

It will take time for tree removal and for the forest to take over the job – growing, seeding new areas, and dying back from others – but the ICO approach gives the forest a head start at creating healthier, more resilient conditions.