The Death of Sampling and the Rise of Forest Architecture

By #forestproud friend, Eli Jensen

Eli Jensen, a Certified Forester and owner of Ironwood Forestry, focuses on improving forest management through innovation. Using tools like high-resolution LiDAR, he and his team enhance the precision of forest data collection, helping identify risks like disease, pests, and wildfires on a tree-by-tree basis, at scale. This technology is key to maintaining forest health and resilience in the face of climate change. Jensen's work is part of the innovative tech solutions emerging in sustainable forest management practices, helping foresters and land managers effectively and accurately balance environmental and economic goals while supporting long-term planning for climate-resilient forests for the future.

That's #forestproud.

Forestry has long relied on sampling methods to manage large expanses of forested land.

However, with the advent of advanced technologies such as LiDAR and remote sensing, a new paradigm is emerging: forest architecture. This innovative approach shifts the focus from traditional sampling to managing forests at the individual tree level, offering an unprecedented level of precision in forest management. This article explores the concept of forest architecture, its benefits, challenges, and the transformative potential it holds for the forestry profession.

The Traditional Approach: Sampling

Sampling has been the cornerstone of forestry management since Carl Schenk opened the first school of forestry at the Biltmore Estate in 1896. Foresters extrapolated plot data from a fraction of the forest to make informed decisions about the entire forest.

While this method is cost-effective and time-efficient, especially for large-scale operations, it comes with inherent limitations. Sampling only looks at a small portion of the forest. In some cases, it observes less than 1% by area. Critical details about individual trees, such as their health, species composition, and precise location, are often generalized, leading to less accurate management decisions.

The Emergence of Forest Architecture

Forest sampling methods have not kept pace with the changing needs and increasing complexity of forest management. As remote sensing technology continues to advance, so does the level of detail and information that it can provide.

Much of remote sensing technology to date has been about improving what we’re already doing. Regression modeling is used to estimate metrics not captured, usually DBH, and stands are still managed based on stand averages. Eventually, the information provided by remote sensing advances to a level where new possibilities emerge. It's not just about improving traditional methods; it enables entirely novel approaches to forest management.

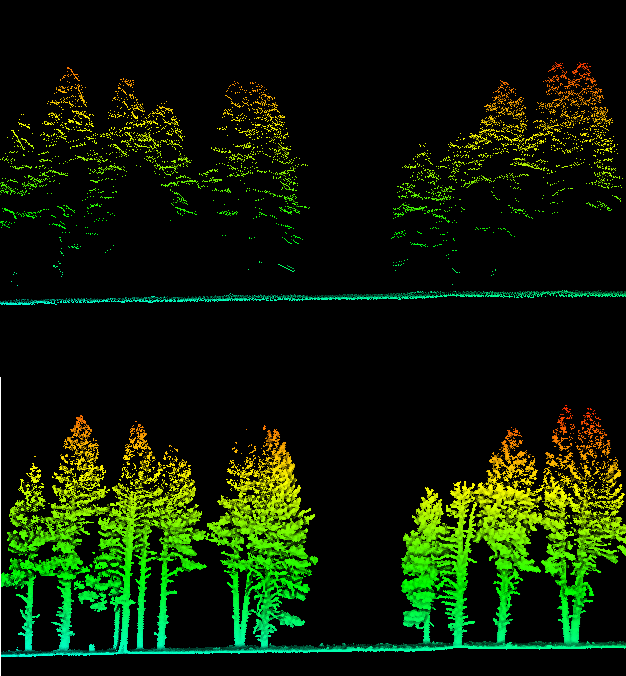

Whether it’s LiDAR or photogrammetry if we can capture all of the parts of a tree (stem, branches, crown, etc.), AND that capture is of a high enough resolution, AND assuming we can reliably segment the data of that tree from others, we can start thinking at the census level rather than at the sample level. First, we can directly measure several features for all trees, which provides a census-level inventory. Second, and undoubtedly more important, we can make decisions and manage forests at the individual tree level. Now we’ve achieved census-level management.

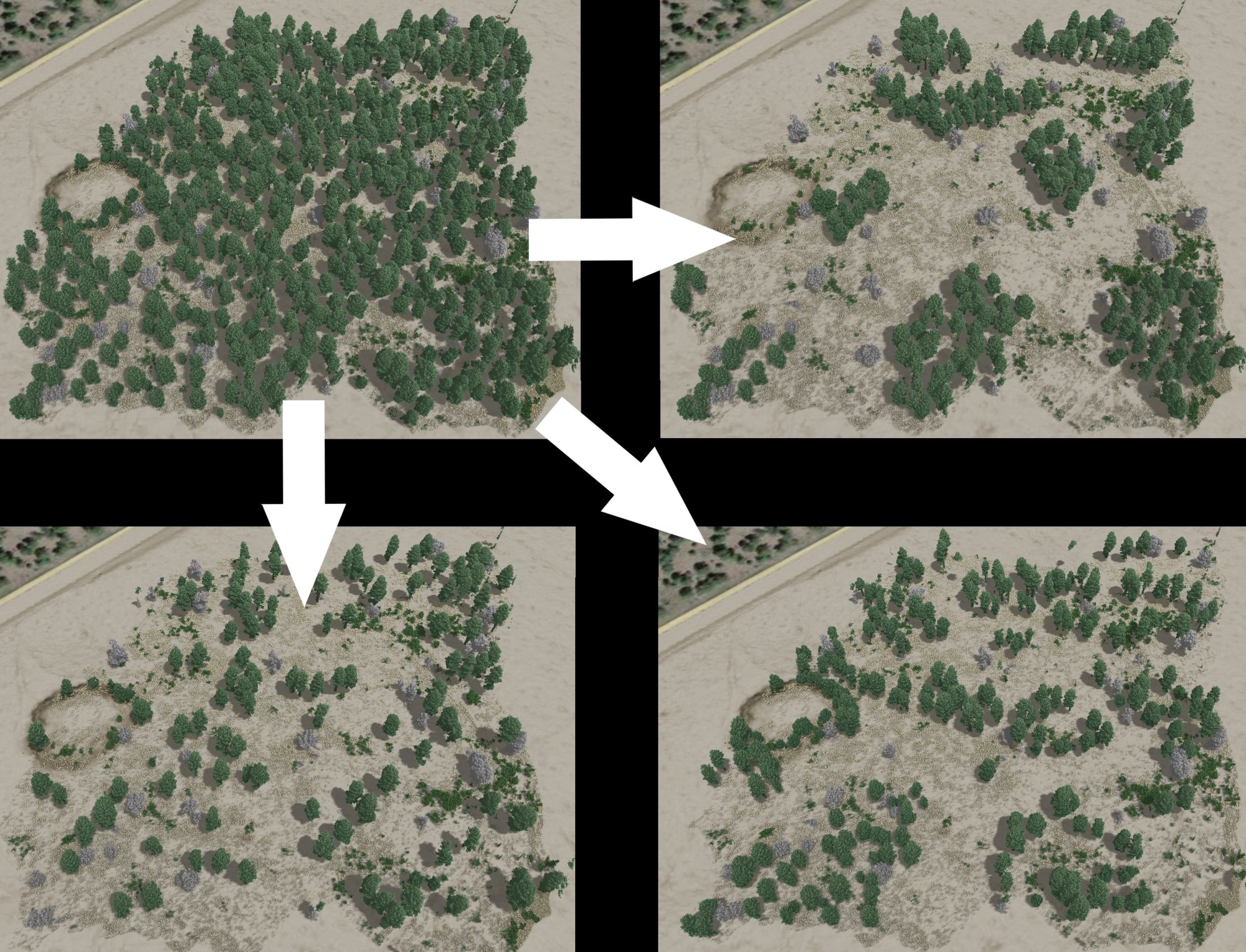

Imagine a standard GIS interface, with your data layers panel on the left. In that data panel are thousands of layers, each one an individual tree with all of its attributes (species, DBH, height, height to crown, crown diameter, defect, etc.). You can “implement” a project, whether it’s a classic timber sale or restoration work, simply by clicking trees “on” and “off.” You can tinker with them until the outcome is exactly as desired, both visually and by census-level data. This is what I am calling forest architecture.

What is Forest Architecture?

When an architect designs a building, they deal in details. Nothing is sampled. Every door, every wall, every window, and every utility is planned to a fraction of an inch. Now we can manage our forests with a similar level of precision.

Forest architecture is a new approach to forest management that involves the dynamic and detailed design of forests at the individual tree level. Utilizing advanced technologies like LiDAR and remote sensing, this method allows for precise mapping, measurement, and management of each tree, enabling foresters to create tailored strategies that optimize forest health, productivity, and ecological balance.

Challenges of Managing at the Tree-Level

While forest architecture offers numerous benefits, it also presents significant challenges. The first challenge is data acquisition. Collecting high-resolution data for every tree in a forest using LiDAR requires expensive equipment and specialized skills. Currently, this is being done from the ground and on foot. In addition, it simply is not a reality yet in many dense forest types.

The second challenge is communicating data to field operations. What good is designing a forest on the computer if that cannot be effectively communicated back on the ground? In open ponderosa pine stands, it may be possible to display this information two-dimensionally on a tablet and successfully identify trees on the map with trees on the ground. In dense and structurally complex forest types, there’s currently little chance of doing this successfully. This will only be possible in other areas once augmented reality technology matures.

The third challenge is how to organize and manage this new information. The writing of the software itself is not challenging. There are dozens of companies or more doing so, but they need to know what to build. That will require foresters to work with software developers to communicate how to translate individual tree data into usable data and develop new methodologies and insights on what tools are needed to collect the appropriate information. This involves a steep learning curve for both sides and a shift in mindset from traditional forestry mensuration practices to more data-driven technology approaches.

Unlocking New Capabilities

Despite these challenges, forest architecture unlocks a range of new capabilities that can revolutionize forestry management. While it will never be better than the census level, I believe it is the future of forest management... We can only begin to understand the potential of forest architecture and how it will shape forest management. Here is the first round of ideas.

- Precision Silviculture: Projects can be designed to meet diverse resource objectives. Then, management actions can be planned to ensure silvicultural prescriptions are implemented with precision.

- Future Visualization: Detailed data on planned management activities can be used to create 3D visual representations of future forest conditions (Figure 2). This helps stakeholders envision the short- and long-term effects of different management strategies, aiding in decision-making and planning.

- Optimize Operations: Census-level cut-tree data can be used to optimize logging operations and minimize impacts.

- Optimize Snowmelt: Tree placement and density can be planned to maximize snow retention. This is crucial for water yield management in regions dependent on snowmelt for water resources.

- Growth Modeling: Detailed individual tree data supports more accurate growth models, allowing for precise predictions of forest development over time. This aids in planning harvests, assessing forest productivity, and managing forest resources sustainably.

- Fire Modeling: By understanding the structure and composition of a forest at the individual tree level, forest architecture enhances fire modeling efforts. This helps in predicting fire behavior, designing firebreaks, and implementing fuel reduction strategies to mitigate wildfire risks. Fire can be modeled for different management outcomes.

- Education and Training: No level of 3D modeling can replace field time for students and young professionals, but detailed and dynamic digital twins of forests allow opportunities to train in the off-season and in diverse forest types while also allowing students to see the outcome of management instantly.

Implementing Forest Architecture

In 2021, Ironwood Forestry presented a five-acre LiDAR scanning demo to the Coconino National Forest, which led to the full-scale 3,250-acre Pumphouse Cross Boundary Restoration Project. This forest restoration project surrounds Kachina Village, just 10 minutes south of Flagstaff, Arizona. This project is in partnership with the Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management (AZDFFM) under a Good Neighbor Agreement and might be the world’s first census-level management project. SAF member John Pelak, a forester with AZDFFM says, “The fine-scale resolution and quantity of data produced has nearly limitless potential to redefine how both the public and forest managers interact with and manage forest resources.”

Every tree in the project will be scanned with a ground-based backpack LiDAR scanner, segmented, and measured digitally. Silvicultural prescriptions will be applied to the digital model, visualized, and adjusted as needed. The final version will then be marked on the ground with paint.

Like any other pioneering effort, this project has had its challenges. Existing Simultaneous Location and Mapping (SLAM) algorithms needed adjustments for this use case, but once the LiDAR manufacturers and developers understood the requirements, the fix was straightforward.

Since the project started in November 2023, weather posed challenges with fieldwork needing to be timed between snowstorms. Another major challenge was geolocating and stitching all the scans together over such a large area, which many said couldn’t be done. The first inclination was to utilize backpack scanners with integrated GPS units, but manual ground control points proved to be more effective.

Now that the hardware and software issues are resolved and the weather is cooperating, the project is progressing well. As of writing this article, over 500 acres have been successfully scanned, georeferenced, merged, and measured: nearly 50,000 trees! The project is set to be completed by September 2024.

Fitting into the Big Picture

While it's undeniably cool to scan forests with lasers and build 3D models, there's an important purpose behind these technological advancements. This isn't just an academic exercise; it addresses significant management challenges, and not a moment too soon.

One of the most pressing concerns facing forest restoration in the West is the supply of prepared projects for the industry. Timber sale preparation capacity in Arizona is critically short, with the entire 4 Forest Restoration Initiative heavily relying on contractors like Ironwood Forestry.

The Pumphouse Project is the first step towards a reliable digital system. The next step is a way to communicate project design details to operators without paint, potentially through augmented reality (either a headset or transparent digital screen on the windshield of harvest equipment).

In the face of staffing shortages and low field capacity, this technology allows fewer technicians, or forest architects, to achieve more with fewer resources. The ability to prepare projects quickly, effectively, and on short notice is essential for meeting both land managing agencies’ needs and the industry’s demands.

Furthermore, this approach addresses the uncertainty of outcomes inherent in tablet marking (DxP+), logger's select (DxP), and even traditional marking methods. By leveraging detailed, digital models, the Pumphouse Project aims to provide clear, precise, and consistent information that enhances project design and operational efficiency.

SAF member Mark Nabel, a silviculturist on the Coconino National Forest says, “Even when a complex prescription is clearly understood by a well-trained marking crew, it is impossible to visualize the mark on the ground at the scale necessary to determine whether structural objectives are being met at the stand level."

"Having census-level tree data, combined with each tree’s precise spatial location on the ground, can drive both the development of prescriptions and the subsequent implementation of those prescriptions. Nuances can be added to prescriptions at the sub-stand level and prescriptions can be tested in front of a computer screen before a marking crew ever sets foot in the field.”

In essence, forest architecture not only modernizes forestry management but also ensures sustainability and efficiency in meeting the increasing demands of forest restoration and timber production. It bridges the gap between cutting-edge technology and practical forestry needs, setting the stage for more robust and responsive forest management systems in the future.

Future Advancements and Next Steps

The future of forest architecture is bright, with ongoing advancements in technology and methodology. As LiDAR and remote sensing technologies continue to evolve, data acquisition will become more efficient and affordable. The potential for more efficient scanning is significant, with innovations like subcanopy drone flights, swarm drones, and better sensors that offer increased penetration and higher points per second. Combining LiDAR scanners with cameras for hyper-realistic coloring and Gaussian splatting will provide even more detailed and accurate forest models.

Machine learning and data analytics advancements will further enhance our ability to process and interpret large datasets, making forest architecture more accessible and scalable. Collaboration between forestry professionals, researchers, and technologists will be crucial in driving these advancements. By working together, these stakeholders can develop new tools, techniques, and best practices for implementing forest architecture on a larger scale.

Educational institutions and professional organizations also have a critical role in this transition. By incorporating forest architecture principles into forestry curricula and continuing education programs, they can prepare the next generation of foresters to embrace this innovative approach, ensuring that the profession remains at the forefront of technological and methodological advancements.

Forest Architecture Marks A New Era in Management

By embracing the precision and detail offered by advanced technologies, foresters can achieve more effective, sustainable, and resilient management outcomes. While the transition to forest architecture presents challenges, the potential benefits are immense. From enhancing forest health and resilience to optimizing resource utilization and supporting climate change mitigation, forest architecture offers a transformative approach to managing our invaluable forest resources.

As the forestry profession continues to evolve, embracing forest architecture will be crucial in meeting the complex and dynamic challenges of the 21st century. By harnessing the power of technology and data, we can ensure that forests remain healthy, productive, and sustainable for generations to come.

Original article written by Eli Jensen for SAF's The Forestry Source, June 2024

Many benefits of using social media came to light. Perhaps the most basic: social media provides a way to educate and communicate with others, which was important to all of the participants.

Many benefits of using social media came to light. Perhaps the most basic: social media provides a way to educate and communicate with others, which was important to all of the participants.