Wood Innovation Following Natural Disasters

Even before its release date in June 2024, the remake of Twisters was one of the year’s biggest cinematic moments. All spring, our feeds were full of tornado anticipation: ads on streaming platforms, new country music hits, gifs shared across social media, and even billboards turned upside down and tattered like a storm had recently rolled through. The global marketing campaign just happened to coincide with what’s often considered peak tornado season in the middle of the United States—an area nicknamed “Tornado Alley”, a place where scenes of leveled homes and clouds of debris swirling mid-air, unfortunately, don’t require CGI technology.

Now that we’re a few months out from the height of Twisters, online conversations have waned. It’s not unlike what happens in the news cycle after disasters hit a local area. But those areas are still recovering long after the headlines fade. Like many post-disaster recovery processes, debris removal can take a long time, and because it comes after the height of the storm, the innovative solutions employed to deal with debris are often overlooked. Across the country, wood product innovations are being scaled to keep debris out of landfills. Salvage wood industries, biochar, bioenergy, and compost are just a few of these innovations in recycling, up-cycling, and wood reuse that help to lighten the environmental impact of natural disasters.

There were a lot of tornadoes this year, and not just in the movies.

The release of Twisters also coincided with the realization that 2024’s tornado season would be one of the worst on record across the Great Plains and Southeast. In May, a tornado occurred every day somewhere in the country. While some of this activity is consistent with the shift of El Nino to La Nina, rising global temperatures are causing a trend of tornado activity moving eastward into more densely populated areas.

While the definitive impact of climate change on tornadoes remains unknown, the eastward movement of Tornado Alley represents just one aspect of climate change’s multifaceted impact on natural disasters. In some cases, increased global temperatures contribute to more intense disasters like stronger storms or larger wildfires. In other cases, the frequency of disasters is impacted. In the case of tornadoes, a changing climate is causing an unprecedented reckoning with deadly weather events. When the built environment isn’t designed and constructed in consideration of climate, you end up with a big mess, literally.

Disaster debris: An overlooked cost of climate change.

For many of us, carnage where buildings or forests once stood makes for a dramatic storyline, a compelling reason to head to theaters. But for others, these scenes of destruction are the very real fallout of disasters like tornados, hurricanes, floods, and earthquakes. It can be so severe and so messy, that there’s a term to describe the destruction that follows a catastrophic storm, “disaster debris,” and there are entire economies, government processes, and policies around how to deal with it. The full scope of a natural disaster’s physical impact might not be obvious to those living outside of an area especially vulnerable to these events: that side of things wasn’t shown in Twisters.

It’s easy to hear “debris, think “trash,” and say, “Throw it all away!” But considering the scope and scale of debris left behind after a category five hurricane or magnitude seven earthquake, it's impossible to imagine a landfill large enough to contain it. And there kind of isn’t... Many landfills around the country are projected to fill up within the next two decades.

To put it into perspective, the total disaster debris produced from Hurricane Katrina in Mississippi and Louisiana—only two states out of the seven states with recorded deaths resulting from the storm’s impact—was estimated at 72 million cubic meters. That’s enough debris to fill over 70 football stadiums or to cover 18,000 acres with 1 meter of trash.

It’s true that much—too much—of disaster debris ends up in landfills. In many cases, there’s no other choice: a significant portion of debris is single-use by design or too destroyed to be recycled. But sometimes, it’s just because there’s no existing process for recycling the materials. That’s often the case with woody debris—downed trees, tree limbs, wood from buildings and other sources—which can be recycled and SHOULD be recycled wherever possible. When landfilled instead of recycled, woody debris decays and generates carbon dioxide and, worse, methane, a greenhouse gas over 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere.

Diverting woody debris from landfills could be a key step in meeting emissions goals while creating additional opportunities for communities to rebuild and regrow.

Where there’s wood, there’s a way.

Downed trees might be the image most of us associate with heavy storms. Of all disaster debris, about 30% is vegetative wood waste—that's untreated, completely recyclable wood ready to be reclaimed and reimagined.

Innovations in wood recycling play an important role in mitigating the financial costs and climate impacts of disaster debris. When trees come down in a community, they rarely get a second life. 15 to 30 million tons of urban and community wood is wasted nationally every year. This wood ends up in landfills, releasing carbon into the atmosphere as the wood slowly rots away.

Following natural disasters, urban and community wood utilization and recycling efforts divert wood from waste streams and landfills, decreasing carbon emissions while creating value and driving new markets.

Salvage wood: From trash to treasure.

Salvaging wood for high-quality products is tough work, but it's a rich opportunity, especially following disasters. Reclaiming woody debris and transforming it into works of wooden art reimagines downed trees as resources and solutions. Salvaging wood reduces wood waste, creates jobs in underserved communities, and stores carbon in long-lived wood products.

Because, after all, in a capitalist society, if we don’t value something, there’s no value in it. Right? Right.

As we mentioned, removing and managing disaster debris is a massive financial undertaking. Offsetting these costs requires some creative thinking and a willingness to explore new markets.

#forestproud friends are leading urban wood efforts.

In California, Street Tree Revival and Deadwood Revival Design, two woodworking and lumber companies, are working exclusively with urban trees, milling them into usable lumber and slabs. The outcome is beautiful, one-of-a-kind furniture pieces.

Wood from the Hood and Room & Board also have a great collaborative partnership. Room & Board, a Minnesota-based retailer, is known for its modern elegant furniture lines. In 2023, Room & Board kept the equivalent of over 300 trees out of the waste stream—their goal is to divert the equivalent of 1,000 trees annually by 2025. Since 2008, the Minneapolis-based company Wood From the Hood has been creating custom-made furniture and home goods from reclaimed urban wood. After its high-quality pieces became a fixture in homes and commercial spaces, the business waited for the opportune time to grow and pivot. They imagined a line of furniture that would save more landfill-bound trees, sequester carbon emissions, and supply local homeowners with budget-friendly products. Now a key production partner with Room & Board, Wood From the Hood meets the production needs for many of their high-end furniture lines.

These companies are just a handful of the growing urban wood network focused on elevating woody waste to its highest and best use. There's a ton of high-quality wood languishing in landfills and waste-streams than is currently used and elevating that wood into high quality furnishings and home decor gives that wood a second life. The artisanal results speak for themselves. Check out #urbanwoodnetwork and #urbanwoodmovement on IG for some lovely examples.

Composting: Waste wood that’s good for gardens.

Unfortunately, following especially impactful disasters, wood waste might hardly resemble a log. Think twisted tree limbs, broken branches, and a smattering of twigs. So, salvaging down timber for lumber is sometimes out of the question.

If you have an at-home compost pile, you might know where we’re going with this. Waste wood makes great brown matter! And yard residual industrial compost facilities are poised to handle the scale of vegetative debris following intense weather events. Often, these facilities sell compost or mulch to agricultural or landscaping operations, enriching soil quality and carbon sequestration potential in the process.

While industrial composting and mulching facilities often face challenges sorting contaminated waste, the presence of a facility in at-risk areas is a step closer to ensuring climate-smart recycling of disaster debris.

Bioenergy: Wood that keeps the lights on.

Natural disasters that affect densely populated areas often get the most news coverage. Of course, tornadoes, hurricanes, floods, and wildfires ravage rural locations too, with wide-ranging impacts well beyond the disaster itself. Businesses and communities that depend on natural resources can suffer greatly in the face of these disasters. A single storm system, wildfire, or tornado can shutter local businesses and, sometimes, halt entire local economies. Additionally, those dead, damaged, or dying trees create additional dangers – they can fuel the next round of natural disasters. Removing downed and damaged timber is an essential wildfire mitigation measure known as “fuel reduction.”

Removing blown-down or damaged timber that can’t be used as lumber still provides value to humans and the environment, but it’s often very expensive. Where some people see destroyed timber and expensive recovery projects, we see biomass. We’re talking about organic material rich with potential, especially for creating renewable energy.

Bioenergy is just that: organic material (aka biomass) transformed into transportation fuels, heat, and electricity. Ethanol, biodiesel, and burning to create steam-powered electricity are just a few bioenergy sources sourced from downed timber. Bioenergy can create new renewable sources of energy (trees regrow!) increase the flexibility and reliability of the electric grid and create new markets that help pay for the costs of removing the damaged wood in the first place. Moreover, when bioenergy is burned in a controlled manner, filter technology can remove over 95% of pollutants that would otherwise enter the air.

There’s a network of existing infrastructure for collecting biomass for bioenergy all around the country. One example is a partnership between Lassen National Forest in Northern California and a nearby power plant, Honey Lake Power. In a single year, the national forest can provide 140,000 dry tons of wood per year—wood collected after fuel reduction projects or destroyed in wildfires—to support local energy production.

Biochar: Turning up the heat on climate solutions.

Energy isn’t the only opportunity for woody debris to make a positive climate impact. It might sound counterintuitive, but we like biomass because it’s full of carbon. One reason we want to make use of it before it can decompose (and emit CO₂ into the atmosphere) is so that we can harness that carbon for

good things, like improving soil quality.

One way to do this is by converting biomass into biochar, a highly porous, charcoal-like substance that’s basically made of carbon. To create biochar, wood is burned at super-high temperatures without the presence of oxygen.

Once mixed into soil, biochar has some pretty magical (actually, very scientific) benefits.

- Soil aeration

- Moisture retention

- Nutrient makeup

On top of this laundry list of benefits, biochar is so pure it doesn’t degrade, meaning it’s a permanent solution for improving soil health and preventing carbon dioxide from entering the atmosphere. While we are using state-of-the-art technology and new vocabulary words, this concept is not new. Indigenous cultures have used charred organic matter to improve soil quality for thousands of years.

Good in theory, great in practice... But challenges still exist.

Reusing or recycling vegetative waste might be the most straightforward aspect of sustainable debris management. But they still face roadblocks. Community composting efforts efforts often face permitting challenges. Biochar, bioenergy, and artisanal furnishings require infrastructure investments. However, they've proven to be significant climate solutions, and application within disaster debris recycling only exponentially increases their positive impact.

Luckily, there are organizations across the country investing in salvage processes and recycling technologies. The forest sector is one of the leading sources of this innovation, from developing harvesting machines to efficiently extract timber to applying LiDAR, AI, and drone technologies to debris management.

Overcoming financial, technological, and policy barriers associated with wood waste recycling will necessitate greater public understanding and support of potential solutions. Media that carries a cultural impact like that of Twisters is the perfect opportunity for this kind of public education. So, who knows... Maybe we’ll see a sequel that shows the other side of natural disasters: debris management and climate change. Until then, we’ll jump in where the story left off... We can’t promise Jo and Bill get together after the cameras cut, but we can assure you there’s work to be done in the wake of one of the worst tornado years on record, and forest climate solutions are a key part of the cleanup.

That’s #forestproud.

We can’t wait to dive deeper into some of these topics in the future! Let us know:

- What questions do you have about bioenergy and biochar?

- What stories from the sector should we cover in future blogs?

- What are you and/or your organization doing to contribute to waste wood recycling?

Shoot us a note: info@forestproud.org.

In November 2023, Memphis Urban Wood Academy participants focused on what makes urban and community wood uniquely scalable in Tennessee. The event took place at the heart of the Memphis Botanical Gardens and was full of dedicated practitioners working on solutions to divert urban and community wood from the waste stream into circular, regional bio-economies.

In November 2023, Memphis Urban Wood Academy participants focused on what makes urban and community wood uniquely scalable in Tennessee. The event took place at the heart of the Memphis Botanical Gardens and was full of dedicated practitioners working on solutions to divert urban and community wood from the waste stream into circular, regional bio-economies.

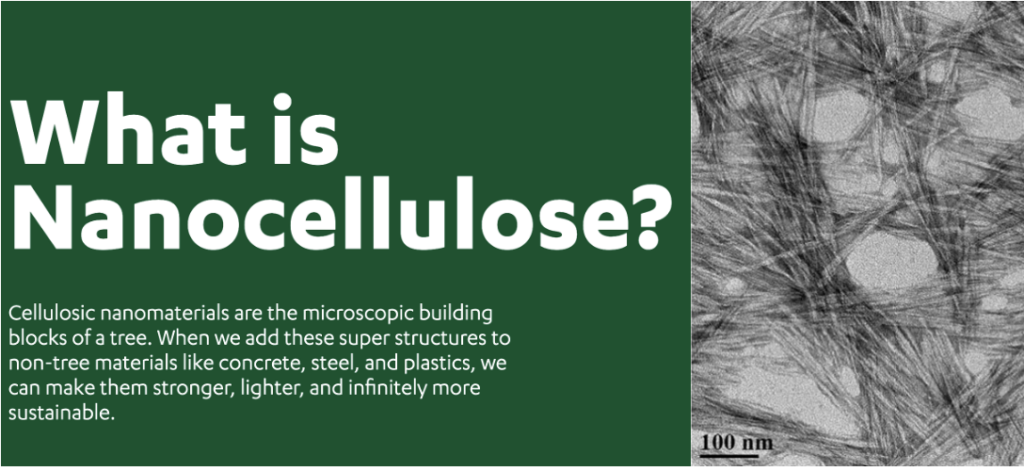

Forests provide habitat for thousands of species, regulate climate, purify air and water, and support the livelihoods – and lives – of millions of people. As one of the planet’s most significant carbon sinks, forests play a pivotal role in regulating our climate by absorbing and storing carbon dioxide (CO2), so ensuring forests remain resilient and healthy is an essential part of climate change mitigation strategies.

Forests provide habitat for thousands of species, regulate climate, purify air and water, and support the livelihoods – and lives – of millions of people. As one of the planet’s most significant carbon sinks, forests play a pivotal role in regulating our climate by absorbing and storing carbon dioxide (CO2), so ensuring forests remain resilient and healthy is an essential part of climate change mitigation strategies.