Inspiring the Next Generation

We love seeing #forestproud make a real-world impact, and one recent project out of Wisconsin is a perfect example of what happens when content, education, and mission-driven organizations come together.

Last fall, Into the Outdoors, an Emmy Award-winning “edutainment” series focused on outdoor and science education, teamed up with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR), the LEAF program (Wisconsin’s K–12 Forestry Education Program), the USDA Forest Service – Forest Products Lab, and the Wood Innovations Program to launch a new video series celebrating the importance of forests and forest products in our daily lives.

Timed with Forest Products Month in October 2024, the series was designed to inspire young minds, support classroom learning, and raise awareness of how forests shape our communities and our future.

Turning #forestproud Content into Curriculum

One of the new episodes was directly inspired by our own #forestproud article, Wood Innovations: Shifting from Plastics to Planet. (Read the HERE) The story was adapted for younger audiences and transformed into a dynamic classroom lesson tailored for elementary students, making abstract ideas accessible and exciting for kids.

This type of translation from story to screen to school is exactly the kind of impact we’re proud to support.

A Collaborative Mission

Into the Outdoors began as a collaboration between Discover MediaWorks and the Wisconsin DNR, with a shared goal of getting kids away from screens and into nature. Over time, the partnership has grown, and today, it includes ongoing work to promote sustainable forestry, forest products, and the future of the forest workforce.

According to the producers, the video series reached more than 800,000 viewers across traditional and streaming platforms, not including PBS distribution. The episodes and lessons were shared with hundreds of schools, educators, and students throughout the region via trusted education platforms such as the National Educational Telecommunications Association (NETA) and Stride, Inc.

Supporting Classrooms and Communities

Gina Smith, Resource Specialist for the Wisconsin Center for Environmental Education and the College of Natural Resources at UW–Stevens Point, shared: “Driven by our goal of enriching students and sustaining forests, LEAF was excited to create hands-on lessons for students of all ages to support the new Into the Outdoors Forest Products and Wood Education episodes. We’ve enjoyed sharing the episodes and lessons with over 6,000 Wisconsin educators via conferences, workshops, and our newsletter, the LEAFlet.”

She added a quote from LEAF’s long-time DNR partner, Kirsten Held, who said it best: "Young people and natural resources are Wisconsin’s greatest assets. Together, we have the privilege of supporting the growth of both so they thrive and continue to support our state in the future.”

Positive Feedback and Growing Impact

Hailey Rose of Into the Outdoors noted the strong response from the education and forestry communities alike: “The response has been incredibly positive. The forestry community has embraced these topics, recognizing them as essential conversations for both current and future generations. Educators and students alike have found the content engaging and relevant.”

She added: “Our team remains deeply committed to supporting the forest industry and is always seeking new partnerships with organizations and individuals who share our passion. Moving forward, we plan to focus on topics such as technology, workforce recruitment, environmental stewardship, and responsible forest management. We are proud to be part of the #forestproud community and look forward to continuing this important work.”

Interested in seeing the lessons? View the curriculum bundle here

Real-World Impact, Real Future

Real-world impact is at the heart of what we do at #forestproud. We’re honored to collaborate with partners like Into the Outdoors, LEAF, and the Wisconsin DNR, organizations that are not only amplifying the value of forestry but also inspiring the next generation to see themselves as stewards of the land.

Read more about this series and Into the Outdoors here

Together, We Speak Forests, to inspire, to educate, and to grow the next generation of stewards.

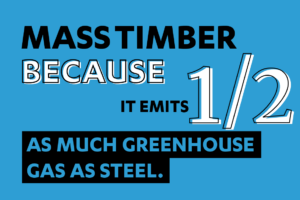

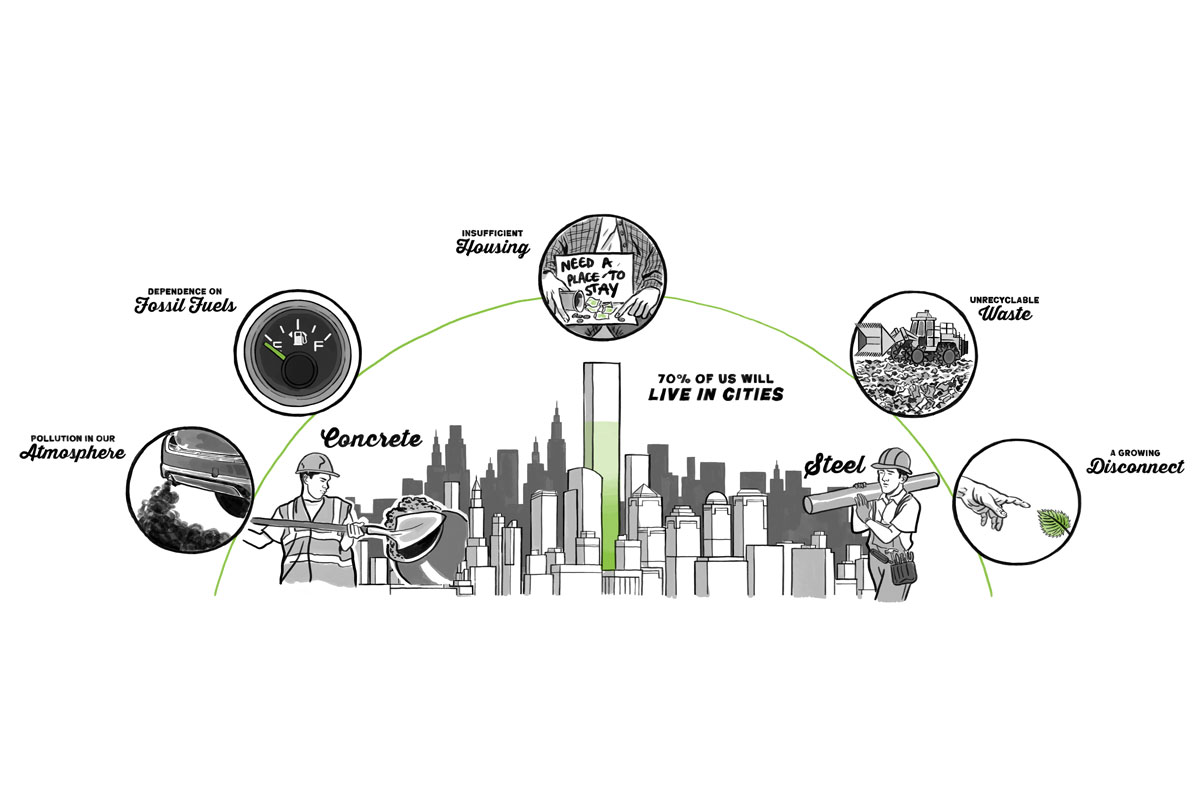

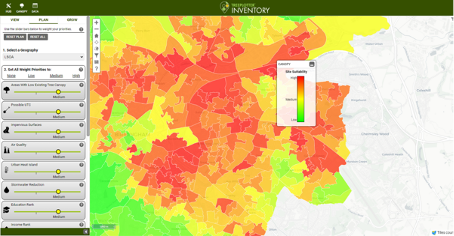

(Check out the full writeup that inspired this graphic from Ohio State University)

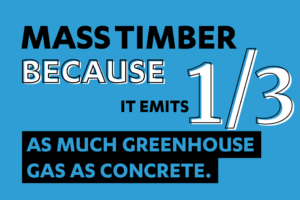

(Check out the full writeup that inspired this graphic from Ohio State University)