By Tony Mazza, Natural Resources Policy Specialist, SAF.

In late September 2022, I had the pleasure of visiting Huntington Forest at SUNY’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry (ESF). The higher peaks in the area were already displaying picturesque fall foliage, setting the scene for a pleasant weekend. I was invited by Dr. Marianne Patinelli-Dubay, who is the Environmental Philosophy Program Coordinator at ESF and SAF Adirondack’s Chapter Chair. During my weekend at Huntington, I had the immense pleasure of spending an afternoon with forester Mike Federice, who manages ESF’s forest properties in the Adirondacks. He is also SAF Adirondack’s Chapter Chair Elect. Federice gave me a generous tour of Huntington, which included a black bear sighting, local trivia, splendid vistas, and most impressively, a walk through the forest’s demonstration and research sites.

The back-to-back demonstration sites brought to life textbook silviculture treatments, some serving as important research projects attempting to address challenges forests face in northern latitudes. I was inspired by Federice’s knowledge, insight, and optimism around the future of the forest sector, and so I invited him to share more about his work with ESF.

Tony Mazza (TM): Hi Mike. To begin, would you introduce yourself?

Mike Federice (MF): I’m Mike Federice, a Forester with SUNY ESF Forest Properties. I manage ESF’s Adirondack Forest Properties in northern New York. Prior to working with ESF, I worked in industrial forestry and procurement in upstate New York and New England. I have always enjoyed the outdoors, which is what led me to become a forester.

TM: Can you tell us a bit more about ESF’s properties in the Adirondacks and the type of work carried out there?

MF: SUNY ESF maintains 20,000 acres of forest land in the Adirondacks, in addition to 4,000 acres in central New York. There are four different properties spread across the Adirondacks, each with their own defining characteristics and specific uses which make them unique. The primary purpose of the Forest Properties is to promote opportunities for teaching, research, and demonstration.

The properties are regularly used as an outdoor classroom, which is an indispensable learning tool for hands-on teaching. The properties also provide a setting for long- and short-term research across a multitude of topics like forestry, ecology, wildlife, biogeochemistry, and beyond. There are various examples of forest management techniques as a means of demonstration on some of the properties as well. Public recreation is currently permitted in some capacity on portions of three of the four Adirondack properties.

TM: During our tour of the Huntington Forest, you discussed how your research plots are addressing some of the leading threats to forests in the Adirondacks. Can you discuss some of the challenges you’re addressing and what your research suggests so far?

MF: The primary challenge we are facing at this time is associated with the effects of beech bark disease. Beech saplings are prolific throughout the understory across the majority of our hardwood stands. These saplings have little—if any—opportunity to develop beyond small diameter pulpwood. Since the saplings are already established in the understory, they impede regeneration of desirable species (i.e., sugar maple, yellow birch, red oak, white pine, hemlock, red spruce). In our more recent timber harvesting, we found it necessary to remove the beech saplings from the understory during harvesting in order to open the understory for desirable regeneration. This has been accomplished during logging using a feller buncher and a prescribed threshold for cutting beech saplings (i.e., 1” DBH or > 5 ft. tall). Timber harvest areas employed with this level of beech sapling removal are still in the early stages of regeneration and are being closely monitored as regeneration begins to appear. We have also seen that heavier cutting intensities help initiate a competitive advantage for regeneration of desirable species over beech.

Another challenge we are facing is climate change. Shorter and milder winters pose major concerns for winter logging. This is especially important here in the Adirondacks where many areas can only be accessed during frozen conditions. The cost of constructing a road only for winter use is considerably cheaper than a summer access road; this is particularly important in areas with low timber value. A long-term concern associated with climate change is the transition of tree species ranges. The Adaptive Capacity Through Silviculture (ACTS) study at Huntington Forest is intended to evaluate strategies for managing forest stands for climate change mitigation and adaptation. The ACTS study also includes a “Transition” area. Within the Transition blocks, tree species more characteristic of warmer sites will be planted and monitored for success. In many cases these species' current range does not include Huntington Forest, however, given temperature projection models, it is expected their ranges will shift to higher latitudes and elevations.

Other challenges the Adirondack properties are facing include white pine decline, forest tent caterpillar, and spongy moth. There have been recent management activities in areas affected by all three of the above concerns. Hemlock wooly adelgid, emerald ash borer, and beech leaf disease are also knocking on our door with anticipated management challenges that may facilitate additional research and demonstration projects for us. Another concern of mine is having an adequate contractor base of loggers and truckers in the future. The general trend in recent years has been a decrease in the number of crews available for logging, which may pose a challenge for us to successfully complete forest management projects.

TM: Given the research you’re doing, it’s clear you are thinking about what the future holds for the forest sector. What opportunities do you think are in store for forestry and forest management?

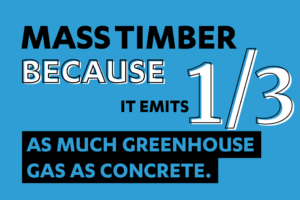

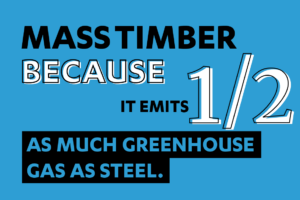

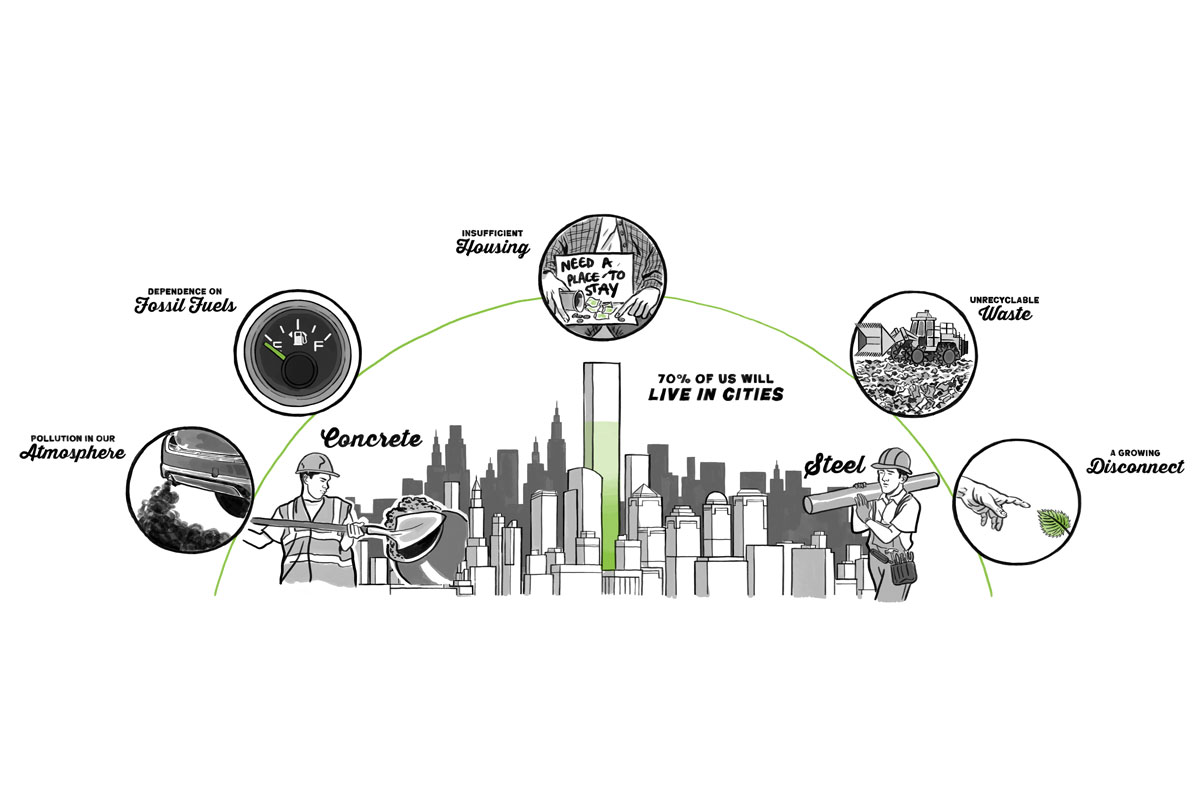

MF: I think there are more opportunities than ever for forestry and forest management. As a society, we are beginning to focus on sustainability and renewable resources. To me, this should mean a growing demand for forest-based products over traditional plastics, fossil fuels, steel, and concrete. I’m hopeful that forestry is recognized by our youth as an avenue for sustainability to help increase recruitment into the field.

TM: ESF is first and foremost a school and a research institution—and a strong one at that. On the topic of the future, can you talk to us about the work you do with students?

MF: On the Adirondack properties, we provide opportunities for field trips and tours of research projects and demonstration areas for ESF classes, as well as groups from other institutions. We are also able to facilitate research areas for students looking for specific sites on the properties with relevant data; we maintain extensive records going back many years that are often used by researchers. Last but certainly not least, Forest Properties often employs a summer crew to help with field work. This is a phenomenal opportunity for students and recent college graduates to gain boots-on-the-ground experience through a variety of forest and natural resources management projects.

In a time when our forests face such grand challenges and opportunities, it’s critical to have forestry professionals who are thinking creatively and strategically about the future of the sector. Central to that task is fostering a new generation of forestry professionals who are passionate and adaptive. We are grateful to Mike Federice and Dr. Marianne Patinelli-Dubay for their forward-thinking service to SAF and the profession.

Original article for the Forestry Source, January 2023 edition

__

__

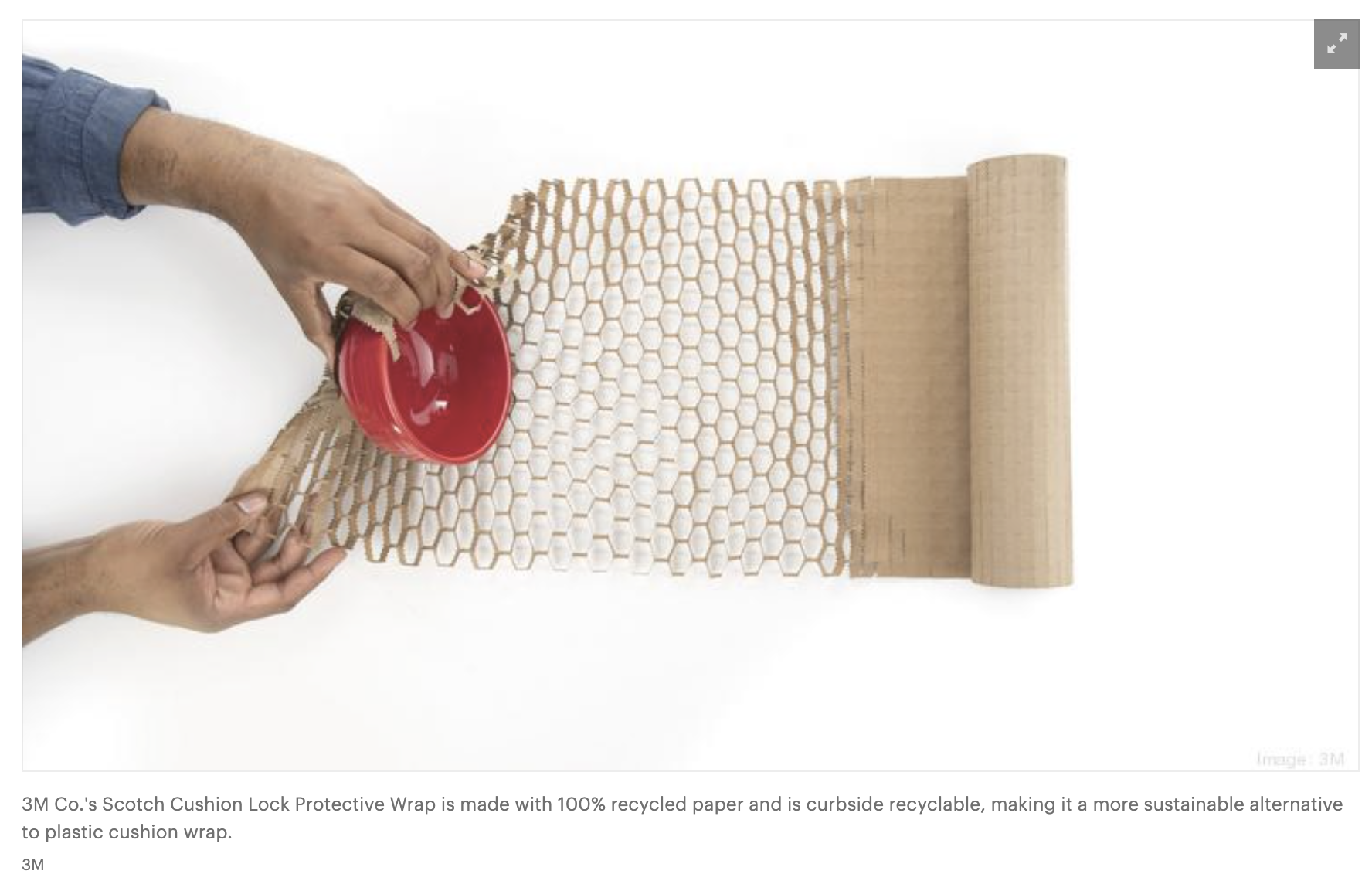

) means that the full cycle of forests and wood products store carbon and have the greatest potential to lessen climate change impacts and keep carbon locked away in forests and wood. From constructing tall buildings to enhancing materials at the microscopic scale, wood products of any size can have big, positive environmental impacts in the fight to limit climate change.

) means that the full cycle of forests and wood products store carbon and have the greatest potential to lessen climate change impacts and keep carbon locked away in forests and wood. From constructing tall buildings to enhancing materials at the microscopic scale, wood products of any size can have big, positive environmental impacts in the fight to limit climate change.